Sen. Robert Byrd dies at 92

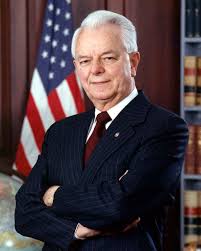

robert byrd

Sen. Byrd talks to members of the media before the resumption of President Clinton's impeachment trial. Byrd was openly hostile over Clinton's affair with White House intern Monica S. Lewinsky.

Robert Carlyle Byrd, the West Virginia Democrat who was often called this generation's conscience of the Senate for his devotion to the system of constitutional checks and balances and the prerogatives of power, died Monday. He was 92.

Byrd, who served longer than any member of Congress in U.S. history and cast more congressional votes than anyone since taking office in January 1959, died at about 3 a.m. at Inova Hospital in Fairfax, Va., a spokesman for the family said.

Byrd, who served longer than any member of Congress in U.S. history and cast more congressional votes than anyone since taking office in January 1959, died at about 3 a.m. at Inova Hospital in Fairfax, Va., a spokesman for the family said.

He was admitted to a Washington-area hospital late last week suffering from what a spokesman said was believed to be heat exhaustion and severe dehydration as a result of the high temperatures in the capital.

As president pro tem of the Senate, he was third in line for succession to the presidency. The post of president pro tem now goes to Sen. Daniel K. Inouye, a Democrat from Hawaii.

West Virginia Gov. Joe Manchin III, a Democrat, will appoint someone to finish Byrd's term, which ends in 2013.

Byrd's death marks another milestone in the demise of a postwar generation of "Old Bulls" who ran Congress for decades. Many of them — such as Pete V. Domenici (R-N.M.) and John Warner (R-Va.) — have retired. Ted Stevens (R- Alaska) lost his 2008 bid for reelection in the face of corruption charges. Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass.) died last year.

In recent years, the wheelchair-bound Byrd was not as strong a presence in the Senate as he once was, making rare speaking appearances. Byrd showed up at a Senate hearing in May and read a statement cautioning colleagues against severely limiting use of the filibuster, a device he used to hold the Senate floor for 14 hours and 13 minutes in an unsuccessful filibuster of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Renowned for carrying a copy of the U.S. Constitution in his left shirt pocket to brandish at colleagues and constituents, Byrd had a deep commitment to history. A master of Senate rules, he was by turns protective and disruptive of procedure, slowing debate with long, florid orations that invoked Greek philosophers, Roman generals and the Founding Fathers. But he could also pierce debate with a pointed comment.

When politicians were scrambling to create a Department of Homeland Security after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, he asked his colleagues, "Have we all completely taken leave of our senses? If ever there was a time for the Senate to throw a bucket of cold water on an overheated legislative process that is spinning out of control, it is now. Now!"

And as the Senate prepared to debate authorization for war in Iraq in early 2003, Byrd thrilled antiwar activists with his lament — "Today, I weep for my country" — and gave a speech that would be reprinted in several languages and posted on many websites — no small achievement for a man who did not use a computer. "We stand passively mute in the United States Senate, paralyzed by our own uncertainty, seemingly stunned by the sheer turmoil of events," he admonished. "We are truly sleepwalking through history."

He was sworn in as a congressman 17 days before President Harry S. Truman left the White House in 1953, and died as a senator nearly six decades later. In three terms in the House and nine in the Senate, he said his proudest legislative achievement was the defeat of the balanced budget amendment in the mid-1990s, which he likened to "putting an ugly tattoo on the head of a beautiful child." The "beautiful child" was the Constitution, and he was convinced that amending it by stripping Congress of its constitutional power of the purse would mar it forever. So when Congress passed the line-item veto in 1996, giving presidents blue-pencil authority over congressional appropriation, Byrd called it "one of the darkest moments in the history of the republic." Two years later, the courts agreed that the law crossed a line, ruling it unconstitutional.

Byrd was not always a champion of liberal causes. He had come of age as a member of the Ku Klux Klan and cast a "no" vote on the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 that prohibited discrimination against African Americans and others. He later renounced his actions in both cases and called his membership in the KKK "the worst mistake of my life."

Byrd was aghast whenever the Senate acceded to a president's wishes without debate or question. He was a stickler for the constitutional provisions for checks and balances that left Congress, known as "the people's house," in the lead on appropriations and taxation.

He was not afraid of standing up against presidents, even if they were fellow Democrats. Just days after the 1968 Tet offensive, the surprise assault against South Vietnamese and American forces that tipped U.S. public opinion against the Vietnam War, he told President Lyndon B. Johnson that American intelligence had failed, that "we should have known, we should have foreseen what happened." Johnson exploded. Byrd held his ground. "Mr. President, I didn't come here to be lectured," he recounted. "I'm no 'yes man.'"

Decades later, Byrd rose up to protect Congress' prerogatives against incursions of another Democratic president. Shortly after Barack Obama was sworn in, Byrd objected to the proliferation of White House staff czars that Obama chose to oversee policy areas such as healthcare.

"The rapid and easy accumulation of power by White House staff can threaten the constitutional system of checks and balances," Byrd said.

But if he was a protector of the Senate's role in balancing the power of the executive branch, he also was a deft manipulator of the legislative system. As chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, Byrd was notorious for steering federal funds — and sometimes whole federal agencies — to West Virginia, where so many buildings and highways bore his name that the watchdog group Citizens Against Government Waste voted him "Alpha Porker." Columnists derided him for dismantling the government piece by piece and sending it to West Virginia: the FBI's fingerprint center to Clarksburg, an Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives weapons-tracking center to Martinsburg, a series of NASA-related projects to Wheeling Jesuit University.

Byrd didn't seem to mind the criticism. He often bragged that when he was in the state Legislature in 1947, West Virginia had four miles of divided, four-lane highways, but that by his eighth term in the Senate in 2004, the number was up to 1,033 miles. Only once — when he tried to uproot 6,000 employees of the Central Intelligence Agency and relocate half of them to West Virginia — did Congress balk. Dealing with Byrd, said former Rep. Dave McCurdy (D-Okla.), then chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, was "almost like a meeting you have with a foreign government."

So fierce was Byrd's control of the institution that former First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, on winning a Senate seat from New York in 2000, sought his counsel on how to navigate the Senate. Byrd, who had been openly hostile over her husband's dalliance with White House intern Monica S. Lewinsky, taught her well. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Byrd helped Clinton secure $20 billion for New York's recovery. "Count me in as the third senator from New York," he said at the time.

On election night 2000, when Byrd, then 83, was reelected with his largest margin ever — a 78% majority, carrying all 55 counties and all but seven of the state's 1,970 precincts — he remarked: "West Virginia has always had four friends: God Almighty, Sears Roebuck, Carter's Little Liver Pills, and Robert C. Byrd." (He later dropped Sears from the list, complaining about inadequate service on a heater.)

In 2006 he was reelected to an unprecedented ninth term in the Senate, winning 64% of the vote.

Byrd, who in various stages of his career served as the Democratic whip, the majority leader, Appropriations Committee chairman and Senate president pro tem, was also the chamber's unofficial historian, writing a two-volume history of the institution with the assistance of Senate historian Richard Baker.

As president pro tem of the Senate, he was third in line for succession to the presidency. The post of president pro tem now goes to Sen. Daniel K. Inouye, a Democrat from Hawaii.

West Virginia Gov. Joe Manchin III, a Democrat, will appoint someone to finish Byrd's term, which ends in 2013.

Byrd's death marks another milestone in the demise of a postwar generation of "Old Bulls" who ran Congress for decades. Many of them — such as Pete V. Domenici (R-N.M.) and John Warner (R-Va.) — have retired. Ted Stevens (R- Alaska) lost his 2008 bid for reelection in the face of corruption charges. Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass.) died last year.

In recent years, the wheelchair-bound Byrd was not as strong a presence in the Senate as he once was, making rare speaking appearances. Byrd showed up at a Senate hearing in May and read a statement cautioning colleagues against severely limiting use of the filibuster, a device he used to hold the Senate floor for 14 hours and 13 minutes in an unsuccessful filibuster of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Renowned for carrying a copy of the U.S. Constitution in his left shirt pocket to brandish at colleagues and constituents, Byrd had a deep commitment to history. A master of Senate rules, he was by turns protective and disruptive of procedure, slowing debate with long, florid orations that invoked Greek philosophers, Roman generals and the Founding Fathers. But he could also pierce debate with a pointed comment.

When politicians were scrambling to create a Department of Homeland Security after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, he asked his colleagues, "Have we all completely taken leave of our senses? If ever there was a time for the Senate to throw a bucket of cold water on an overheated legislative process that is spinning out of control, it is now. Now!"

And as the Senate prepared to debate authorization for war in Iraq in early 2003, Byrd thrilled antiwar activists with his lament — "Today, I weep for my country" — and gave a speech that would be reprinted in several languages and posted on many websites — no small achievement for a man who did not use a computer. "We stand passively mute in the United States Senate, paralyzed by our own uncertainty, seemingly stunned by the sheer turmoil of events," he admonished. "We are truly sleepwalking through history."

He was sworn in as a congressman 17 days before President Harry S. Truman left the White House in 1953, and died as a senator nearly six decades later. In three terms in the House and nine in the Senate, he said his proudest legislative achievement was the defeat of the balanced budget amendment in the mid-1990s, which he likened to "putting an ugly tattoo on the head of a beautiful child." The "beautiful child" was the Constitution, and he was convinced that amending it by stripping Congress of its constitutional power of the purse would mar it forever. So when Congress passed the line-item veto in 1996, giving presidents blue-pencil authority over congressional appropriation, Byrd called it "one of the darkest moments in the history of the republic." Two years later, the courts agreed that the law crossed a line, ruling it unconstitutional.

Byrd was not always a champion of liberal causes. He had come of age as a member of the Ku Klux Klan and cast a "no" vote on the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 that prohibited discrimination against African Americans and others. He later renounced his actions in both cases and called his membership in the KKK "the worst mistake of my life."

Byrd was aghast whenever the Senate acceded to a president's wishes without debate or question. He was a stickler for the constitutional provisions for checks and balances that left Congress, known as "the people's house," in the lead on appropriations and taxation.

He was not afraid of standing up against presidents, even if they were fellow Democrats. Just days after the 1968 Tet offensive, the surprise assault against South Vietnamese and American forces that tipped U.S. public opinion against the Vietnam War, he told President Lyndon B. Johnson that American intelligence had failed, that "we should have known, we should have foreseen what happened." Johnson exploded. Byrd held his ground. "Mr. President, I didn't come here to be lectured," he recounted. "I'm no 'yes man.'"

Decades later, Byrd rose up to protect Congress' prerogatives against incursions of another Democratic president. Shortly after Barack Obama was sworn in, Byrd objected to the proliferation of White House staff czars that Obama chose to oversee policy areas such as healthcare.

"The rapid and easy accumulation of power by White House staff can threaten the constitutional system of checks and balances," Byrd said.

But if he was a protector of the Senate's role in balancing the power of the executive branch, he also was a deft manipulator of the legislative system. As chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, Byrd was notorious for steering federal funds — and sometimes whole federal agencies — to West Virginia, where so many buildings and highways bore his name that the watchdog group Citizens Against Government Waste voted him "Alpha Porker." Columnists derided him for dismantling the government piece by piece and sending it to West Virginia: the FBI's fingerprint center to Clarksburg, an Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives weapons-tracking center to Martinsburg, a series of NASA-related projects to Wheeling Jesuit University.

Byrd didn't seem to mind the criticism. He often bragged that when he was in the state Legislature in 1947, West Virginia had four miles of divided, four-lane highways, but that by his eighth term in the Senate in 2004, the number was up to 1,033 miles. Only once — when he tried to uproot 6,000 employees of the Central Intelligence Agency and relocate half of them to West Virginia — did Congress balk. Dealing with Byrd, said former Rep. Dave McCurdy (D-Okla.), then chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, was "almost like a meeting you have with a foreign government."

So fierce was Byrd's control of the institution that former First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, on winning a Senate seat from New York in 2000, sought his counsel on how to navigate the Senate. Byrd, who had been openly hostile over her husband's dalliance with White House intern Monica S. Lewinsky, taught her well. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Byrd helped Clinton secure $20 billion for New York's recovery. "Count me in as the third senator from New York," he said at the time.

On election night 2000, when Byrd, then 83, was reelected with his largest margin ever — a 78% majority, carrying all 55 counties and all but seven of the state's 1,970 precincts — he remarked: "West Virginia has always had four friends: God Almighty, Sears Roebuck, Carter's Little Liver Pills, and Robert C. Byrd." (He later dropped Sears from the list, complaining about inadequate service on a heater.)

In 2006 he was reelected to an unprecedented ninth term in the Senate, winning 64% of the vote.

Byrd, who in various stages of his career served as the Democratic whip, the majority leader, Appropriations Committee chairman and Senate president pro tem, was also the chamber's unofficial historian, writing a two-volume history of the institution with the assistance of Senate historian Richard Baker.

He rose to speak often and eloquently on the Senate floor about the institution's history, giving more than 100 lectures on Senate history topics. The speeches created a certain buzz in Washington, but colleagues rarely waited through the orations. For the most part, he wrote the speeches himself, and they carried the lyrical tone and the sweeping sense of history of a self-made man.

Born in North Wilkesboro, N.C., on Nov. 20, 1917, as Cornelius Calvin Sale Jr., he was a year old when his mother died during the influenza pandemic and his father sent him to be raised by an aunt and uncle in West Virginia. Vlurma and Titus Dalton Byrd re-christened him Robert Carlyle, and raised him in a background "as grindingly poor as that of any American politician," according to Michael Barone's "The Almanac of American Politics." They encouraged him to study, hoping he would escape the harsh poverty of coal mine country. And study he did, teaching himself to read, memorizing history lessons, becoming the valedictorian of his high school class at age 16. But they had no money for college.

Entering the job market at the height of the Depression, he took work in any field he could find — gas station attendant, meat cutter, produce salesman, welder. During World War II, welders were in demand at ship construction sites, and so off he went, building Liberty and Victory ships in Baltimore and Tampa, Fla. After the war, he came home to West Virginia.

In 1946, he ran for a seat in the state House of Delegates, campaigning, according to the Almanac, "in every hollow in the county, playing his fiddle and even going to the length of joining the Ku Klux Klan." He quickly renounced his membership but it would be years before he renounced segregationist politics — in 1967 he voted against confirmation of the Supreme Court's first black justice, Thurgood Marshall.

None of this hurt him politically in West Virginia. In fact, he never lost an election. When a congressman retired in 1952, Byrd won the seat. By 1958, with Dwight D. Eisenhower in the White House, despite opposition from the United Mine Workers Union and the coal companies, he won election to the U.S. Senate.

While in the state Legislature, he attended college but according to his Senate biography would not receive his degree in political science from Marshall University until 1994, some 60 years after high school. While in the Senate, he went to law school at night, graduating from American University at 46, receiving his diploma from the 1963 commencement speaker, President Kennedy. The years of protracted education made him zealous about knowledge. Even while campaigning in impoverished West Virginia, he infused his speeches with an old-fashioned, stem-winding oratory, calling on Cicero or Thucydides as needed, sometimes to the puzzlement of his constituents.

He was elected Democratic whip in 1971. In 1977 he was elevated to majority leader, serving there until 1981, and again from 1985 to 1989. He abandoned what he called "the grubby work" of being Senate majority leader in 1989, assuming the job he had long coveted: chairmanship of the Senate Appropriations Committee, where he vowed to become West Virginia's leading industry. In 2000 alone the appropriations bill included more than $1 billion of spending in West Virginia, much of it attributable to Byrd's steering.

In his later years, beset by health problems and mourning the loss of his wife Emma in March 2006 after 69 years of marriage, Byrd grew more publicly emotional. He cried on the Senate floor at the news that Kennedy had been diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor. When Kennedy suffered a seizure in Obama's post-inauguration lunch on Capitol Hill, Byrd was so upset that he too was taken out of the event in a wheelchair.

And he all but monopolized a hearing on tainted pet food from China, rhapsodizing over his Shih Tzu. So poignant were his outbursts that Democratic colleagues discussed — but did not implement — a plan making Byrd the emeritus chairman and naming Washington's Patty Murray the "acting chairwoman."

He is survived by daughters Mona Byrd Fatemi and Marjorie Byrd Moore, five grandchildren and five great-grandchildren

Born in North Wilkesboro, N.C., on Nov. 20, 1917, as Cornelius Calvin Sale Jr., he was a year old when his mother died during the influenza pandemic and his father sent him to be raised by an aunt and uncle in West Virginia. Vlurma and Titus Dalton Byrd re-christened him Robert Carlyle, and raised him in a background "as grindingly poor as that of any American politician," according to Michael Barone's "The Almanac of American Politics." They encouraged him to study, hoping he would escape the harsh poverty of coal mine country. And study he did, teaching himself to read, memorizing history lessons, becoming the valedictorian of his high school class at age 16. But they had no money for college.

Entering the job market at the height of the Depression, he took work in any field he could find — gas station attendant, meat cutter, produce salesman, welder. During World War II, welders were in demand at ship construction sites, and so off he went, building Liberty and Victory ships in Baltimore and Tampa, Fla. After the war, he came home to West Virginia.

In 1946, he ran for a seat in the state House of Delegates, campaigning, according to the Almanac, "in every hollow in the county, playing his fiddle and even going to the length of joining the Ku Klux Klan." He quickly renounced his membership but it would be years before he renounced segregationist politics — in 1967 he voted against confirmation of the Supreme Court's first black justice, Thurgood Marshall.

None of this hurt him politically in West Virginia. In fact, he never lost an election. When a congressman retired in 1952, Byrd won the seat. By 1958, with Dwight D. Eisenhower in the White House, despite opposition from the United Mine Workers Union and the coal companies, he won election to the U.S. Senate.

While in the state Legislature, he attended college but according to his Senate biography would not receive his degree in political science from Marshall University until 1994, some 60 years after high school. While in the Senate, he went to law school at night, graduating from American University at 46, receiving his diploma from the 1963 commencement speaker, President Kennedy. The years of protracted education made him zealous about knowledge. Even while campaigning in impoverished West Virginia, he infused his speeches with an old-fashioned, stem-winding oratory, calling on Cicero or Thucydides as needed, sometimes to the puzzlement of his constituents.

He was elected Democratic whip in 1971. In 1977 he was elevated to majority leader, serving there until 1981, and again from 1985 to 1989. He abandoned what he called "the grubby work" of being Senate majority leader in 1989, assuming the job he had long coveted: chairmanship of the Senate Appropriations Committee, where he vowed to become West Virginia's leading industry. In 2000 alone the appropriations bill included more than $1 billion of spending in West Virginia, much of it attributable to Byrd's steering.

In his later years, beset by health problems and mourning the loss of his wife Emma in March 2006 after 69 years of marriage, Byrd grew more publicly emotional. He cried on the Senate floor at the news that Kennedy had been diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor. When Kennedy suffered a seizure in Obama's post-inauguration lunch on Capitol Hill, Byrd was so upset that he too was taken out of the event in a wheelchair.

And he all but monopolized a hearing on tainted pet food from China, rhapsodizing over his Shih Tzu. So poignant were his outbursts that Democratic colleagues discussed — but did not implement — a plan making Byrd the emeritus chairman and naming Washington's Patty Murray the "acting chairwoman."

He is survived by daughters Mona Byrd Fatemi and Marjorie Byrd Moore, five grandchildren and five great-grandchildren

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar